“What is grief if not love persevering?”

Film critic and author, Hanna Flint, on mixedness, movies as a healing balm, and why white men are the real tokens

Hi everyone,

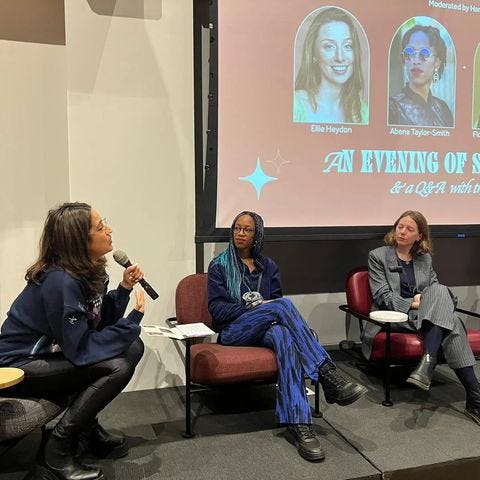

A week late (whoops!), we are back to welcome the lovely Hanna Flint, a London-based critic, author and host who has been covering film and culture for nearly a decade. I have been following Hanna’s work for a while now and I was sooooo excited that she agreed to come onto the newsletter.

In this candid chat, we talk about grieving for lost family members, the films that stick with you forever, and the people who are changing the narrative in the movie biz. We also discuss what it means to be mixed, and the big hypocrisy with conversations around tokenism.

As well as being the author of her fab debut book, Strong Female Character: What Movies Teach Us, Hanna is the co-host of MTV Movies and the weekly film review podcast Fade to Black, the co-founder of The First Film Club event series and podcast, and a member of London's Critics' Circle.

Let us know what you think, and buy Hanna’s book!

Parisa: So you are half-Tunisian, half-British, how do you feel about that language of halves? Because I'm half-Iranian, half-British, and I’m not sure how much I love it.

Hanna: In my book, I quote John Agard’s poem, Half-caste, and I think sometimes there is this question of, am I half a person? I think there is quite a pejorative association with being half. Because I don't feel that way; I consider myself mixed. I prefer that because, for me, it sounds more positive, more multicultural. I suppose everyone has a different relationship to it. It’s only been in the last 10 years or so that I’ve been really exploring that Tunisian side of things. And it’s making me feel whole.

Parisa: I didn’t expect things to get so beautiful and poetic so quickly! That’s such a lovely way to put it. So I also say mixed, but I shy away from saying ‘mixed race’. How about you?

Hanna: I read an interesting book about this by Natalie Morris called Mixed/Other, she’s biracial, black and white. I suppose it is kind of a loaded word, isn’t it? I did a DNA test, and it turned out I've got a bit of Nigerian and Middle Eastern too – a lot of people think I'm Lebanese. I also got Tunisian, and indigenous Tunisian, lots of Spain and Portugal and British, but interestingly enough English wasn’t in there. So I’ve lived my whole life in England, and yet it wasn’t in my DNA. I suppose when you think about what race is, you have categories like Asian, Black, white, and Indigenous. But it's kind of hard to know where you fit in [as a mixed person]. Because the conversation around mixedness and mixed race is so binary. Sometimes you wonder, am I allowed to claim that? And race and ethnicity are very different. So just using the term ‘mixed’ is a really easy way to do it.

“North Africa has been erased from the conversation of what Africa is. It gets subsumed into the Middle East or Southwest Asia.”

Parisa: Yeah, I do think it’s a difficult thing to think around, and approaching labelling is very much different for every person. It’s interesting you did a DNA test. Was there a reason behind that?

Hanna: I suppose, confirmation of what my heritage is. I’d seen pictures of my biological father [who is Tunisian], but I’d never been to Tunisia and for reasons I go into in detail in my book, there is a resistance to connect with my biological father. So I thought this was a less fraught way of having that confirmation. It’s weird, isn’t it? Because I got a DNA test for my brother as well, for Christmas. His results were slightly different, and it’s funny because you can see it manifest in the way we look. I’ve got more brown skin, brown hair, he’s got black hair and slightly paler skin. He looks more Middle Eastern, and I think I look more North African. And I say I’ve got Nigerian in me — it’s like 1.3% — but it's funny how even though we’re both 30 - 40% Tunisian, it is that little bit of Nigerian that makes me feel more African than anything else. But it’s because North Africa has been erased from the conversation of what Africa is. It gets subsumed into the Middle East or Southwest Asia. There's a sense that people who are from that region are not indigenous there, especially when cinema and TV come into play. So for me, just being able to say I’m North African, I’m Tunisian, I’m British, I’m Arab. I don’t mind all these labels, I’m happy to use them and I feel more confident to do that because I’ve got DNA evidence.

Parisa: I’m very tempted to take a test too! I also read you have been taking Arabic classes. I've been taking Farsi classes for the longest time. So it's my mum that is British too. And there’s this idea that they call it your ‘mother tongue’ for a reason, right? When someone's mixed, and it's their mums' language, then they'll be more likely to speak it. But I've got this complicated relationship with Farsi where I'm at a point where I can read and write, but I'm just abysmal at speaking. And I guess I have quite a lot of guilt around it. I was wondering what your relationship with Arabic is like?

Hanna: Living with my mum and stepdad, we had no connection to Tunisia. I went for the first time last year and it was a bittersweet thing. I felt so at home, I felt Tunisian and was welcomed as a Tunisian, told I was one. People told me my English was great! [laughs] But with Arabic, I wish this was something I was taught as a kid when your brain is a sponge. Remember with the Beckham kids? When they were in Spain, when he [David Beckham] was playing for Real Madrid, they were speaking Spanish easily enough. But then when you take them out of there, they suddenly forget. So learning Arabic is difficult for me. I’m doing Duolingo and I did have a Tunisian tutor for a bit. But I didn’t think the way I was being taught was conducive to my learning, and she started talking about a film project — and I was like, okay I’m the one paying for this! [laughs] And with Duolingo, it’s the Egyptian Arabic dialect and not the Tunisian one (which has got bits of French, Italian, Amazigh and other words in there as well). So I'm learning stuff, which is great. But I don’t feel confident saying it out loud. I just feel like I'm gonna say it wrong and butcher it, and I feel like this Western person just appropriating a language. So it’s hard to get outside your own head when you’re doing it on your own. I will say this though, I saw Ramy Youssef do a stand-up show the other day and he was talking about a relationship with his mother, and he said “ḡarīb” and I was like, oh, I understood that! I got the punchline because it was a word I’d learned on Duolingo. And I’m now also picking out words when I watch Arabic films, rather than just watching subtitles.

Parisa: I know that feeling of just getting a small nugget of satisfaction when you understand something, and it feels just brilliant. I also very much relate to what you said about being hesitant to speak. It’s funny because whenever I've learned European languages, I’ve been quite happy to go abroad and hit out with stuff, being terrible at the language. Nobody is expecting me to be good at Spanish. But I do feel that pressure to be good at Farsi immediately, which just isn’t possible when you learn a language.

Hanna: And when you’re doing it later in life, it’s harder to learn because of the sounds. I’m trying to learn French as well. Obviously, the French colonised Tunisia. So I’m thinking, can I bridge the gap, maybe find somewhere in the middle?

Parisa: There must be a lot of crossovers!

Hanna: Yeah, there are lots of French words. Also, there are similar words that have been invented nowadays. Like a CD is a ‘seh-de’ and a laptop is a ‘lab-tohp’ [laughs].

Parisa: Ha! So I’m a huge fan of Isabella Silver’s newsletter, Mixed Messages. You did an interview with her and I loved it, so much resounded with me. She gets everyone to sum up their mixed identity in a word, and you said, ‘evolving’. I wonder how you think your own identity has evolved since writing and publishing your book?

Hanna: Your identity always evolves with new things that you connect to. I find it encompassing now; I feel like I’m not having to pick and choose as much, and I’m allowed to be whole. We're often asked to pick and choose what we are, and a lot of people want to pick and choose for us. So there's more confidence in who I am, my ability to not even have to claim an identity. And that influences my work and how I write. The more I learn about my identity and Tunisia and the world, the better I’m becoming in my criticism. I watched a movie this morning that I’m going to review for Empire, called Harka. It’s set in Tunisia in the aftermath of the Arab Spring. There are things I noticed about it because one, I’ve been to Tunisia, so I recognise certain things, but also understand the socioeconomic circumstances that are at play, and know a bit about the history as well. So when I write my review, I'm coming from an informed position.

Parisa: Along with the cultural influences informing your book, you take a feminist lens to your work. What kinds of texts is Strong Female Character in conversation with?

Hanna: One of the biggest influences was Roxanne Gay’s Bad Feminist. What I like about her is that she talks in her own voice. I love that she did a chapter on playing Scrabble and what that meant. I did a chapter on basketball and how that influenced me. She talks about cinema through a specific, female lens. I love that she talks about her body, her size, and the experience of assault. For me, it is her openness and honesty, and the idea you can come from an academic space, like she does, but also feel very grounded and accessible. She made feminism accessible. And part of what was really important for my book was to have other voices who have done this work as well. So bell hooks is quoted in there, and she talks about Harmony Korine’s film, Kids, and the way it presents innocence and how it presents men. She talks about how rape is shown, how it's normalised and no one cares. So I feel like I'm in conversation with women who have talked about stuff in the past and who are engaged with the cultural conversation, but also my peers who are doing the work as well. My book is also a natural extension of what I've been doing anyway. As a contributor for BBC Culture, I've done essays on female representation. I did one on the makeover scene in Hollywood films; I’ve looked at Lady Macbeth as this misunderstood feminist hero. There are people like Angelica Jade Bastién who I quote in the book and people like Candice Frederick, who is a good friend of mine. Cinema is a reflection of the world. And we can look at what is influencing it. The book is really looking at those influences of cinema, the good, the bad and the ugly of it.

“You go to the premiere of a ‘white’ film and there’s maybe one or two Black people covering it. Why are marginalised identities still considered niche?”

Parisa: You've been doing cultural criticism for a while. From your perspective, what have you seen that has changed with film, and what has very much remained the same?

Hanna: What has stayed the same is the number of white cis male voices in charge. Especially when it comes to most of the film mags in the UK. You still have them leading the conversation. Obviously, there are white women coming through, but if you look at most of the major film magazines in the UK, I'm pretty sure there is not one person of colour on the editorial writing staff for any of the major sites. Maybe there is now, but it’s not something I have seen. I love Empire, I write for them a lot. But there isn't one person of colour on their editorial staff. There are an increasing amount of conversations about representation opportunities for people of colour, women of colour, people who are marginalised and underrepresented. It's a bit like going through wet cement at the moment, but hopefully, this does mean it will get better. My colleague, Amon Warmann pointed this out recently — at the Creed III junket, every Black outlet is out there covering it, but you go to the premiere of a ‘white’ film and there’s maybe one or two Black people covering it. Why are marginalised identities still considered niche? Especially when it comes to news outlets? If you’re covering cinema, even if it's from a Black perspective, you should be able to interview as many people as you can.

Parisa: And what about in terms of what we're actually seeing in films?

Hanna: Like what’s getting better?

Parisa: Sure! Is there anything you’ve seen lately where you’ve thought, okay, wow, things are moving?

Hanna: We are having far more films with female characters who are being allowed to have the same sort of complex characterizations and narrative journeys as men. I would also say there are films that are more reflective of who women are today. I saw this brilliant film, Other People’s Children, the other day. The question at the heart of the film is about a teacher who doesn’t have children, but who starts a relationship with a North African man with a daughter called Leila. She’s 40 years old and forms an attachment with this child, asking herself, does she want kids? It reminds me of the film Stepmom. Do you remember that? But where Stepmom is positioning it as mother versus step-mum, I thought it was so interesting how this was presented differently. There’s a bit where the lead women talk about not letting men off the hook. I love that, because it’s not about the friction between these two women, the problem is actually the man who’s not doing enough and causing issues.

We’re also starting to see more people of colour being able to do Blockbuster releases, which is amazing. You’ve got Nia DaCosta doing The Marvels, Yann Demange doing Blade, Chloe Zhao won best director for Nomadland. A lot of white people — a lot of white men — are in their feelings about tokenism. You know, people often think, am I just getting this because I’m a token woman? or whatever. I find that interesting because it’s what white men have had for years. They’re the ones who’ve been getting stuff just because of the colour of their skin or gender. Now, the difference is that even if you're picked as a marginalised person to tick a box, you actually have to have the talent to back it up. These people who had no competition before are finally understanding that you can’t be tokenistic and mediocre. So I’m both optimistic and realistic. How do you unpack 100 years of patriarchal, capitalist control of an industry and art? There’s a really tough line around what gets made, and who gets to tell stories. But nowadays, we’re seeing far more diverse voices getting to hold the reins.

Parisa: Is there a film that you always come back to?

Hanna: Probably Love and Basketball. Because that was the first time I saw myself on screen. Even though I was not an African-American young girl, I used to play basketball, I was quite a tomboy and I had all these emotions going on. Basketball was this big thing that made me feel confident in myself and be strong and assertive. A lot of that film shows the psychology of what it means to play a sport, and the times when crying isn’t seen as a weakness. If I used to foul out, I would be so frustrated, I would cry. I often think that’s presented as a weak, female, hysterical trait, but actually, in those moments, it's just an expression of frustration and anger. It can be an expression of passion. Monica, played by Sanaa Lathan, is just so good in this film and [director and writer] Gina Prince-Blythewood is just a queen to me. I love the fact she's got an evolving journey, where she started with that film as her directorial debut to go to do The Woman King now, it's just amazing. She's a perfect example of not underestimating women of colour. Because they are just as capable if not better than the homogenous group, at telling these stories and telling stories from the margins as well.

Parisa: So do you turn to that film when you are looking for comfort? For me, I go to the things I love when I need that. But maybe it’s different for you as a film critic. You must be switched on to work mode whenever you watch films!

Hanna: Yeah, Love and Basketball is a comfort watch, but it's also just one of my favourite films. My grandma died during lockdown. She died during Covid, in a care home, and I watched the entire MCU [Marvel Cinematic Universe] back to front as a kind of safety blanket. That was comforting to me because so many of those stories are about grief and overcoming. There’s that great line from WandaVision that is something like, ‘what is grief, if not love persevering?’ I wrote a piece for the BBC about how those narratives can both be an escape but also present the emotions you might be going through, or are unable to process. It gives you a visual narrative language to be able to relate and allow those notions to come out.

But I am definitely in a position now where I’ve watched so many films that rewatching is not big on my agenda. This is partly imposter syndrome, but there are so many gaps in my film knowledge that I'm trying to fill. I did watch Everything Everywhere All At Once three times — that was my favourite film of 2022. But I think it constantly changes. There are too many good films to pick one. This is why, when I was asked to do the Sight and Sound 100 Greatest Movies list, I didn’t do it. Of all the movies ever made, I'm supposed to pick 10? It made my brain hurt. I'm a conscientious objector.

Parisa: I totally get that. And also, I related to what you said about your grandma. I’m sorry to hear about your loss, that's hard. We also lost my grandma during Covid. But it reminded me of my experience after losing my granddad years ago. When I found out, I was just getting to my partner's house. We were doing long-distance, and he was living with his family at the time. I found out as soon as I arrived and when I got there I went straight up to his room and just hibernated in bed for two days, watching films. It wasn’t so much the messaging of the films that spoke to me, but there was just something about that experience. These films somehow took me through that time and were really helpful. I do think films have so many different roles in our lives.

Hanna: Absolutely. Cinema is so good for your mental health. Many people don't have the language for what they're going through. They might see someone in a film that is dealing with depression and realise that’s what they’re struggling with too. It can also be a balm, there is that escapist quality of going into these fantastical worlds that are so different from yours. I have a lot of anxiety, I get a lot of intrusive thoughts, and sometimes they can be negative, and you end up spiralling and going down a really deep rabbit hole of negativity and beating yourself up. But when you watch a film, your mind is concentrating on that for maybe two hours, and it helps. I always enjoy going to the cinema more than watching movies at home because, at home, you've got your phone next to you. At the cinema, the lights go down, and you're transported. Sometimes it's great when there are people around you, you get that buzz. But even if you're just going on your own, the cinema is such a great escape from life sometimes.