'I'd always railed against the idea of tradition. But maybe tradition is the thing that holds you while you question it'

Alya Mooro on what it means to be your most authentic self, a move away from oversharing, and what romantic relationships can tell us about the world

Hello, and welcome back!

This week, ready yourself for a conversation filled with generous nuggets of wisdom from writer, author, and today’s wonderful newsletter interviewee, Alya Mooro. In this conversation, we turn to matters of the heart and the business of being yourself.

Alya is the author of the brilliant book The Greater Freedom: Life as a Middle Eastern Woman Outside the Stereotypes. She has written for publications including Grazia, Refinery29 and The Telegraph, and has been profiled by the likes of Harpers Bazaar Arabia and Marie Claire Arabia.

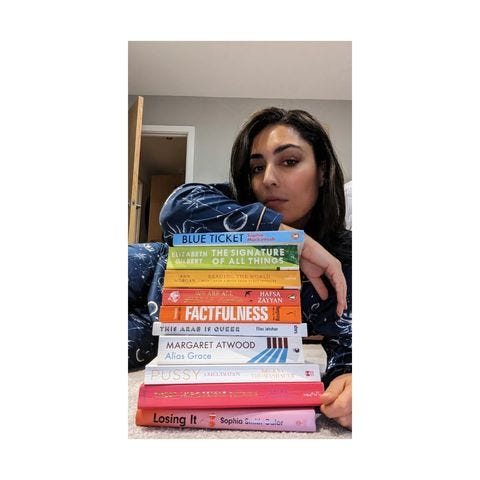

In this interview, we cover so much! Alya talks about making peace with tradition, learning to trust her own voice and the books that helped her heal and grow. She also shares a sneak peek at her exciting upcoming (fiction!) project.

This was such a lovely conversation with many a thought-provoking moment. I really hope you enjoy reading it.

If you want to hear more from Alya, check out her reflective and gorgeously-written newsletter, The Greater Conversation.

How do you describe your heritage?

I always say I'm Egyptian and I was raised in London. That feels like the most accurate way to put it. I was born in Egypt and lived there until I was five. Then I lived there for a year again when I was 12. When I was growing up, I always felt like I wasn’t sure which culture I actually belonged to. Over the years, I’ve spoken to a lot of people who are from Syria or Iraq — countries where it's not as easy to go back – about the difference that makes to their sense of identity. Because I go back to Egypt so often, and I have so many friends there, I could live there if I wanted to. So I really do feel that I'm from both places, even in terms of my accent. I think I’ve often felt a little bit more torn between the two because of that. As an adult, I just feel really grateful for belonging to both places. I think it gives me richness in character, but also in terms of how I see the world, and in terms of what elements of each place I can take and adopt as my own. Sometimes there's the push and pull and confusion, but there's also that real richness.

I totally hear that. My family is from Iran and when I read your book and heard how you’d moved from the UK back to Egypt for a year of school, I thought that was so cool. It’s so beautiful that you could go and spend that time there when you were young — it must have had a really big impression.

At the time, I was like, what on earth is happening? How dare you take me to Egypt? But yeah, I feel so grateful for it now. I spent six months in Egypt last year too, sort of by accident. A lot of my Egyptian friends who live abroad are now starting to have kids and they all cite my mum and how she was so determined to keep me and my brother having a connection to our culture as inspirational. The year we spent living there was so instrumental in cementing that connection. Then also, friendships play a big part in making you feel at home somewhere and spending that year there really gave me that. It's obviously lovely to have family in Egypt, but the thing that really keeps me going back and keeps me feeling so connected are my friendships.

How do you understand yourself in terms of race?

When we need to check boxes, it means we need to look to the outside world to give us a term for what we are. You call it SWANA and then there's MENA; there are all these different ways of talking about the Middle East. It's interesting being in LA right now as well because Arabs are considered white here, even on the census. And I think in the UK, they only added ‘Arab’ to the census quite recently. The outside world, especially when you're younger, does a lot to help you understand for yourself where you're from. Or at the very least, how the rest of the world sees you. So not having something to tick felt strange. I wrote in my book that when I was more tanned I would tick ‘Africa’, because technically Egypt is in Africa, and then if I was less tanned I'd say ‘Other’. I’d find these stupid, weird ways of trying to make sense of it for myself. Now I think of myself as Middle Eastern.

I was also having a conversation with someone Iranian yesterday, and she was saying how growing up, she was made to feel like Arabs were so different from Iranians and that there was a kind of conflict there. Her parents would tell her she can’t date an Arab. We spoke about how we're a minority already and by doing that we’re creating more division and fragmenting ourselves too much. I think it’s important that we see ourselves as part of a wider world, as opposed to trying to have these boxes, but at the same time, we desperately need to be able to see ourselves and to be able to create communities because historically, especially in the diaspora, we have not had that.

Yeah, and it's a really hard question to just throw at you because it is so complicated! I'm still figuring this stuff out for myself.

So what do you think of it?

I have experienced that distinction being made between Arabs and Iranians too, and it’s such a shame because it's so isolating. And the thing is, your regular white English person is not going to make that distinction. They often treat you the same way. So why are we creating that divide between our communities? I think it's hard to choose a category, but I would definitely identify as something other than white because I've been treated that way. And as you say, I think we’re more informed by what other people put upon us, rather than by something we have just decided for ourselves.

Absolutely. It’s quite interesting to see that my friends who live in Iran or who grew up in Egypt or other Middle Eastern countries just don't have this [experience of being racialised] at all, whereas, when you grow up in a country where you are in the minority, you're made to feel like that. Even if it's just through really subtle things. Even if it's not outright racism, it’s the small things that make you feel different.

So this is a good segue into talking about your book, The Greater Freedom. A few years back, I remember DMing you on Twitter before I’d even finished the book, having never spoken to you before, because I loved it so much. I’m wondering if you have had any epiphanies since then, or changed your mind about anything since writing?

It came out just over three years ago, which is insane to me. I feel so different now. When people read it and message me, especially if it's someone I know, I’ll say, ‘Okay, well, just a disclaimer, I'm not that person any more!’ I do feel really disconnected from it, but I also feel that writing it made me who I am now, and I’m still really proud of it. When I was starting to come up with the idea of the book, and while writing, there genuinely was nothing like that out there, especially not for Arab women or with the conversations and questions I was asking. And it was the first time I was really engaging with those ideas. As a world, we're all having these conversations so often now, but at the time we just weren't. So writing that book was my early kind of workings out, my early questions. It was my first step into being who I am now, my first intro into thinking the way I do now. So I'm really proud of it, but it feels like a baby-me who was just starting to think about these things. Now all I do is think about these things.

I think that’s what makes it so valuable because others will be at the point you were at (and I was at), right now. Is there anything in particular about the book that you now feel disconnected from?

I didn't trust my voice or my opinions as much as I do now. So I’d change the fact that I put so much research in there. Research is important, but it almost felt like I was afraid of saying what I thought, or of realising that my feelings and thoughts about things are valid in themselves. I almost felt like I had to give all the reasons why something was in there or include all the people who also feel the same as me. Part of that was for me, to justify it to myself, but I think part of it was also for my family and my parents. Especially when I’m talking about sex. It was like I was saying, ‘Look, it’s not just me!’ If I wrote it now, it would look very different.

One topic that shows up in your work quite often is shame. What is it about shame that you felt it was important to give space to?

Over the years, I've started to understand how shame is used as a controlling mechanism to make us behave a certain way, to make us want to look a certain way, or live a certain way. That shame comes through repetition. It comes through shaming from other people and also from shaming yourself. And that serves to make sure you stay within the status quo. ‘Should’ and ‘shame’ are both words I come back to all the time and I think they are very much linked. In order to get rid of all the external ‘shoulds’ — which is something that is personally very important for me, because I think I hear them quite loudly — we have to be able to get rid of shame. That feeling of shame makes us feel we are abnormal, like we’re doing something wrong, and that keeps us in the ‘shoulds’.

Are you still thinking around these same themes in your current work, or are you starting to ask different questions?

I'm working on a bunch of different things right now. It's funny, having been a journalist in the past [where projects are short term], now I’m working on long-term projects that no one sees for ages, I'm like, ‘am I even doing anything?’ But one of the main ‘shoulds’ I’m thinking about is, how do you live authentically to yourself? That is definitely still occupying my mind. And also the messages we receive around love and relationships, the importance we place on romantic love and questioning traditional structures. I’ve been single for quite a few years, and increasingly my friends are getting married and settling into traditional relationships and all the things that come with that, sometimes including dynamics that have been termed ‘the marriage imbalance puzzle’, which Elizabeth Gilbert talks about in her book Committed. It’s essentially evidence that when a woman gets married to a man, every single aspect of her quality of life decreases and when a man gets married to a woman, every single aspect of his quality of life increases.

If we're not able to have equal romantic-love relationships and able to be respected and seen fully and encouraged fully within that most intimate of settings, then where can we? We can’t. So how is that going to translate to the outside, wider world? That’s what I’m really thinking about right now. Then tied to that is our desirability, how much importance we place on that, our relationships with our bodies, and wanting to be freely sleeping with someone or not. What is the best way to do all this? How can you feel empowered in yourself in a way where you are able to do what you want and live how you like? So I’m seeing romantic relationships as a microcosm of the wider world. A lot of the main project I’m working on at the moment is about that.

“reading increases empathy and fiction allows for that in a powerful way because you are ultimately embodying that character in a way no other medium will allow you to”

It all sounds very mysterious! I'd love to hear anything you can tell me about what you're working on right now?

I'm actually working on a lot of fiction stuff, which has been really interesting and just such a departure from journalism. I overshared a lot in The Greater Freedom, which I have no qualms with. I’m a major oversharer. But I'm really enjoying the ways in which it can feel a lot easier to talk about things that might be scary, or too much to talk about, as yourself. I’m writing a novel and then I’m also writing some TV stuff. I’m enjoying the freedom fiction affords. What’s interesting about fiction is that people think it is made up, but fiction is not fiction, everything is real. Regardless of whether the characters are exactly like you or not, the emotions are real, the energy is real, and the questions you are trying to address through these fictional characters are real. But because it’s not actually me it can feel a bit easier to talk about things. I've been learning a lot about how reading increases empathy and fiction allows for that in a powerful way because you are ultimately embodying that character in a way no other medium will allow you to. So that's been really nice, to be able to really explore a character's full scope of feelings without experiencing a major vulnerability hangover. Although, who knows how I’ll feel after!

Have your mixed geographies informed your fiction writing?

I can't imagine writing a character that is not Arab anytime soon. Just because I feel like we desperately need that representation. We need all the stories we can get. Sure, my experience of life is not going to be the same as every single other Arab person's experience. But hopefully I will encourage someone else to tell their stories so we can have their viewpoint as well. Keeping my dual heritage at the forefront of my work will remain very important to me because I strongly believe in the power of representation. We need to have alternative narratives, and we need to have many of them because ultimately, it's easier to be yourself if you can see yourself.

Is there someone from a SWANA diaspora you find inspiring right now?

I love Salma El-Wardany and her book These Impossible Things. It’s amazing. I’ve always admired how she’s so outspoken. She's so brave, she really gives zero fucks and that’s an energy I need in my life because I do give many fucks.

Amy Mowafi. She’s amazing, she runs MO4, which is the biggest media platform in Egypt. They are always are the forefront of things and she’s doing amazing work for the region.

I've also just come back from filming a documentary in Egypt and we were following Iman and Yousra Eldeeb, two Egyptian sisters who run the first and the biggest modelling agency in the Middle East. They’re doing incredible work to increase the representation of Arab models. Their idea is that in order to be a good model, you have to be yourself. It really ties into my belief that the more people live authentically as themselves, the more permission that gives the rest of us to live authentically as ourselves, and that’s how change happens.

Tahmina Begum, I love her newsletter. She’s also a great friend of mine.

May Calamawy who was the sister on [TV show] Ramy, and was in the new Marvel film, Moon Knight; and Ramy Youssef as well. Ramy has done a lot to push the culture forward and to push for increased representation of Arabs in the mainstream.

You mentioned the importance of being authentically yourself, what do you look like when you are being yourself?

As much as I do feel like I'm authentically myself for the most part, I'm a big-time people pleaser. Big-time. I have these voices in my head that tell me how I should be and what my life should look like. A lot of the work I've been doing on myself over the last few years through therapy, through journaling, has been trying to unlearn that so I can be my most authentic self. What makes it quite difficult sometimes is that there are so many voices, it's hard to even know what you actually want, or what your most authentic version of yourself even is. It can be so clouded and hard to access. So ‘trust’ is my word of the year. Trust is what I've been working on. Trust in myself mainly, and trusting my gut and my instincts so that I can really tune into that voice of inner knowing which tells me who I am and what I need on any given day. Of course, what that self looks like really depends on the mood. I can very easily be a slob in bed for days on end or I can be that fun person at the party. There are so many different versions. My mission is to try to listen to myself as much as possible, regardless of what that version of self looks like on that day.

What is something you have changed your mind about lately?

So many things! I never want to feel like I know everything or that my opinions are final. One of the things I really changed my mind about recently — actually, I wrote a newsletter about it last year when I was spending all that time in Egypt — was that I’d always railed against the idea of tradition. There’s this meme, and it says, “tradition is just peer pressure from dead people.” And I used to think this was so true. Obviously, on some levels it is. But I think being in Egypt and spending time with my grandfather and my parents and friends, I realised how lovely and important tradition is, and how grounding it is. I started to think about how maybe tradition is the thing that holds you while you question it, holds you as you come to your own conclusions about it. It gives you a base, a sense of comfort and security. Without that, we can feel quite adrift and perhaps alone and confused in the world. And I think that’s why we care so much about culture, right? Because it tells you a lot about who you are and where you came from. That’s not to say we should trust traditions blindly, or that we shouldn't question them, but I changed my mind about them; they're not totally useless.

“love can come in all these different ways. It doesn’t have to be this all-encompassing thing that the world tells us it should be.”

What is the cultural artefact that has had the biggest influence on you?

I have two! The first is Essays In Love by Alain de Botton. After a big breakup, my friend told me to read it and the way he wrote about love and intimacy really changed my life. It was written in a way I hadn’t seen before. Spoiler alert: there wasn’t a happy ending where they end up together. So much of it was about the nuances of what builds intimacy. They break up in the book and they each go and get new partners, and that’s life, right? As someone who had grown up seeing many unhealthy relationships and models of, and ideas of, love, and as someone who struggled with codependence and the wounds that make us behave in certain ways, that book really opened my eyes. I realised love can come in all these different ways. It doesn’t have to be this all-encompassing thing that the world tells us it should be.

Then the second is Nawal El Saadawi’s memoirs. There are a few of them, and I read them while writing my book. I had never heard of her at the time, which is crazy to think about now. But she is an OG Egyptian feminist, and she's done so much amazing work. She was speaking about a lot of the things I was thinking about while I was writing, only 50 years earlier. That really validated my own thoughts and feelings. I also heard my grandfather was in class with her, which is just so cool, and she mentioned him in her book by name. It felt really grounding and situating for me that this amazing Egyptian woman, who was 90 at the time — she passed away last year — was thinking, talking and writing about these things so far in the past, and that it was still relevant. It felt disheartening in a way, but also reassuring and validating in others.

On social media, you always share quotes you have highlighted — is there a line or passage that has always stayed with you?

Yes, it’s by Aldous Huxley and it says, “We live together, we act on, and react to, one another; but always and in all circumstances we are by ourselves.” And I love that! Some people find it really depressing, but I don't at all. Because for me, it really just signifies the importance of having a good relationship with yourself, the importance of having your own back, taking care of yourself, and loving yourself. Other relationships with people are great, friendships are so important to me and contribute to having a happy, healthy, fulfilling life. But at the end of the day, no one's in your head with you. No one is in your life with you. And it's important to remember that, and that's what that quote does for me.

This interview was edited for clarity and length.