'We talk about Palestine as an abstract idea, not about Palestinian people'

Illustrator and writer, Aya Ghanameh, on trauma and exile, discovering family video footage, and what she wishes people understood about Palestinian liberation

Hello readers,

The below conversation with Palestinian illustrator and writer, Aya Ghanameh, was recorded on September 27th, 10 days before the present crisis unfolded in Israel and Palestine.

It is heartbreaking to re-read this conversation which feels more poignant than ever. “We will not be perfect victims,” says Aya, describing the dehumanising tropes which have paved the way for the subjugation of Palestinians over the past 75 years.

In an Instagram post, Layla F Saad described her rage and grief over Palestine as a ‘deep primal scream’. As our governments in Europe and North America remind us how little Muslim lives matter to them, it is a sentiment I am sure many of us presently share. It has been devastating to see both Muslim and Jewish people express feeling re-traumatised and unsafe right now; demanding Palestinian liberation, grieving for Palestinian and Israeli families suffering loss, and condemning the current surge in both anti-semitism and Islamophobia is not antithetical.

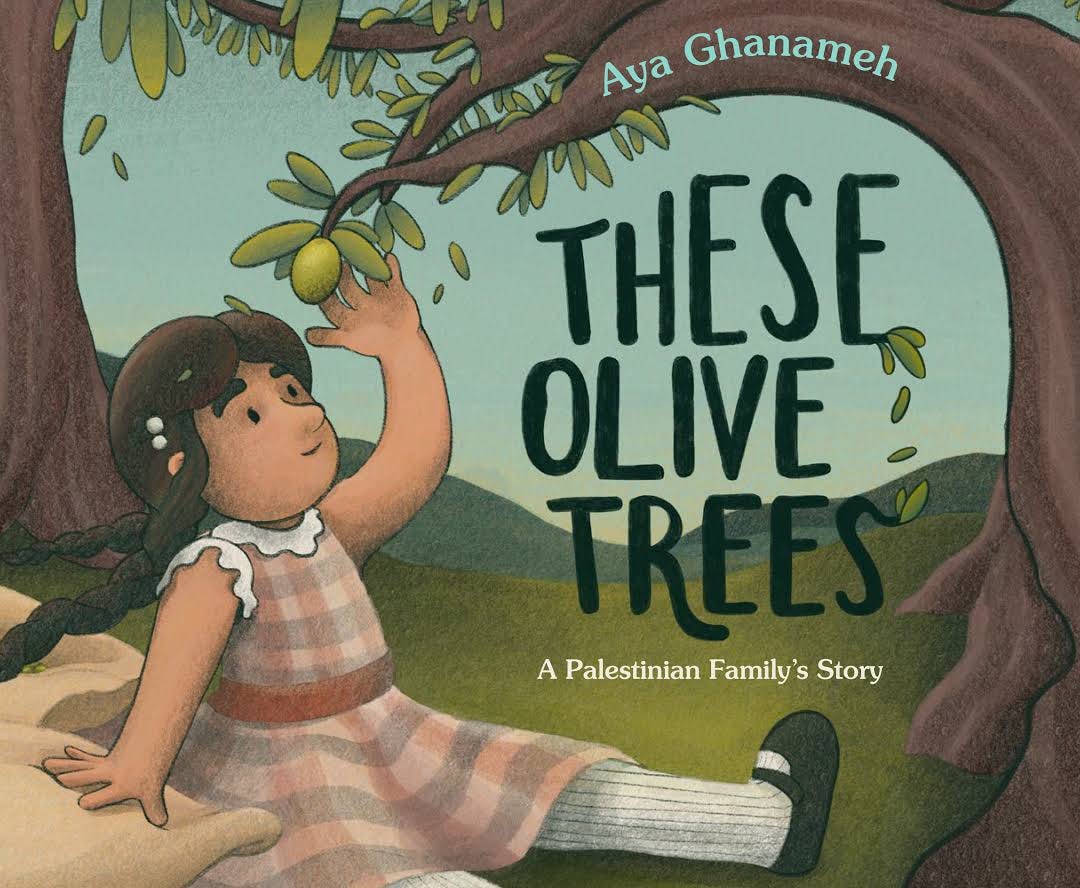

Aya Ghanameh is a Palestinian illustrator, writer, and designer from Amman, Jordan. She received her BFA from the Rhode Island School of Design and is currently a Designer with Penguin Random House at Penguin Workshop. Aya’s work moves away from state-centric ways of thinking to centre the voices of ordinary people in historical and political narratives. Her debut children's picture book, These Olive Trees (Viking Books, 2023), is inspired by the experiences of her family who cultivated her love of the earth throughout her upbringing in exile.

I hope you take something from this conversation with Aya, and that if you have children in your life (and even if you don’t) you consider buying her wonderful book. If you haven’t already, I would also like to use this space to encourage you to write to your MP to demand a ceasefire.

To start us off, I would love to hear a bit about the inspiration behind These Olive Trees.

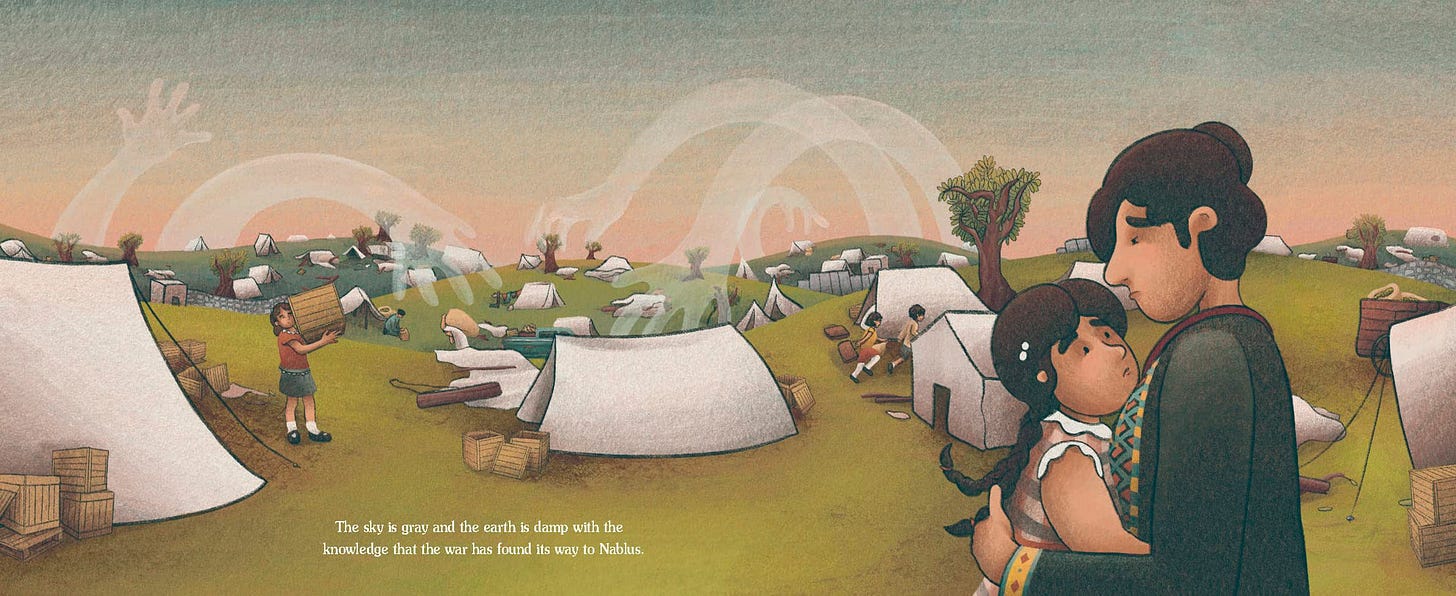

So the book is about my grandmother. She's been an inspiration to me my whole life. She practically raised me. Millions of Palestinians have a very similar story and writing this book was sort of inevitable for me as a young artist coming to the US. I grew up in Jordan and I came here for college. It wasn't until I came here that I had to face Zionist and, basically, the mainstream discourse [about Palestine] for the first time. Because I spent my whole life in Jordan, the only interactions I've had with people outside my community who think that way has been Israeli soldiers at the border. So my work didn't start off being explicitly political when I first came to college as a student. But over time it moved from just pictures to zines and comics. I started incorporating [some of the stuff I was] reading into it, and then gradually it grew more and more political and identity-based. I sort of wound up with this book that I’d produced as a senior in college; it was my senior thesis. I took a class at Rhode Island School of Design called ‘Picture and Word’. The final project was to create a picture book dummy, so to write a manuscript and do a whole sketch dummy. These Olive Trees was that sketch dummy. It’s the story of my grandmother's expulsion from Palestine, and I think it's the typical Palestinian story. I wanted to write something universal to Palestinians, but also universal overall, thematically. Because I think a lot of the time when we talk about Palestine, we talk about Palestine as this obscure abstract idea and we don't focus on Palestinians themselves, who they are as people, and what happened to them.

‘My cousin was murdered when I was six in the West Bank, that is what shaped my understanding of Palestine’

Growing up in Jordan, what was your relationship like with Palestine? And how has that changed over time?

So Jordan has a predominantly Palestinian population. I think 80% of Jordan’s population are Palestinian refugees or people of Palestinian descent, so it was something that's just always been a part of my life growing up. In Jordan, you're asked if you're a Jordanian-Jordanian or a Palestinian-Jordanian. But I don't think I learned much about the language used when we talk about Palestine or the specific political history and all its intricacies until I went to college and started actively seeking out classes that taught it. What I knew before that came from the lived experience of my whole life. As I got older, I had to go out of my way to learn how to articulate my lived experience and talk about it properly. But in terms of awareness growing up, my cousin was murdered when I was six in the West Bank, so I think that is what shaped my understanding of it. It was the initial thing that made it a big subject in my life.

I’m so sorry to hear this, Aya. You also mentioned not really coming across Zionism before you came to the US. How do you look after yourself in the face of all this, particularly as someone who is now a public figure with this incredible online voice?

I think I've been in the spotlight for Zionists for a while. I’ve been on Canary Mission since 2020. It’s a Zionist, right-wing website that doxxes Palestinian and Muslim students, primarily in the US. It makes a whole profile about them in order to smear them. I've been on that since I was a student and it's meant to deter career prospects. It's been several years, and it's not affected me necessarily. Or maybe it has. But I think the reality of being Palestinian is so much more extreme than the words of some weird sock puppet account online. Online sort of feels fake to me. I don't feel like it's real. And it hasn't had much material effect on my life. I am employed, so I think things are okay. But I am genuinely always reminded of the fact that I am privileged enough to be here and to get an education whereas my family did not have that opportunity. The majority of them still live in the West Bank. I think that if they had a platform, or if they could speak English, they would be doing as much as they could. I'm just doing what I can from the position I'm in at the moment. I'm not really deterred by anything. I don't know if survivor's guilt is the right word but I feel like if I don't do anything, then it's just doing them a disservice. And even then, I don't feel like I do enough. So in terms of online harassment, it's fine.

Do you speak with your family about the work you do?

Not really, I kind of just do it and then share it. But I don't think a lot of them fully grasp what I am doing. For example, with this book, I don't think they really understood that it was an actual thing that is published until it came out, if that makes sense. I don't think they know what illustration means. They're like, ‘Oh, so do you paint?’ It's not really something I talked to them about. But I interviewed my grandmother and her siblings for other projects that I may want to work on one day. I don't think they fully get what it's for either. But they're always happy to talk. They love talking about Palestine even if it's traumatic, they just start going on for hours. So I'm grateful to still have them in my life, for them to still be alive and able to share all of that with me.

‘Media discourse dehumanises Palestinians and makes us out to be subhuman… their story is that we are too underdeveloped and uncivilised to be able to run a country’

What is something you wish more people knew about being Palestinian?

I wish more people focused on Palestinians as people rather than talking about us in an abstract way. A lot of the media discourse dehumanises Palestinians and makes us out to be subhuman. That is an actual part of the Zionist mission. They need to keep us dehumanised and seen as subhuman in order to keep spreading their message. I want people to know that a lot of what happens to us, both in an effort to suppress and destroy the nation, is held on and passed down. Zionists hope we will forget what happened to us. There is a famous quote from the first Israeli prime minister, saying ‘The old will die, and the young will forget.’ I want people to understand that 75 years is not a long time, and we are living through our grandparents' trauma. We are people, and we are producing so much culturally. There’s so much writing and culture coming out of a younger generation of Palestinians who didn’t necessarily live through the Nakba but have survived it generationally. It’s so important to keep amplifying these voices because they are actively being censored. This goes back to the idea we’re not people because the Zionist narrative heavily relies on Palestinians being uncivilised. At its essence, their story is that we are too underdeveloped and uncivilised to be able to run a country. The cultural production of Palestinians and the celebration of that cultural production directly counters that. We are civilised, we are capable, we are competent, and we have an identity of our own. So that's something I think is super important. Last weekend, I was actually at the Palestine Writes Literature Festival, which is why I'm thinking so much about that. I've never been in a space where there has been so much celebration of Palestinian culture. I was surrounded by writers, artists, painters, photographers. It was just crazy! There were like 1500 people there. I've just never been in a space like that before, which is why I'm thinking about this a lot.

Beautifully put! One thing I loved about your author's bio is the references to Arab food — you live in New York where you ‘overspend on Arab restaurants’. I can relate! All my money goes on food. What is it like to be Arab in New York? Do you feel a connection to other Arabs in the city?

I've been here for a year and a bit now. Before that, I was in Rhode Island for college. These are my first experiences with the US. Going from Jordan to Rhode Island was really weird. It's a really white town, really small. It's not really a city. It's just a college town with Brown University and RISD, there's nothing else really going on. Coming straight to New York has been so surreal; there's an actual community here. That's why I mentioned food because it's something that I didn't think I would be able to find. So I have just been going to any place that I can and trying to see if they make food that is remotely close to my grandmother's. But in terms of community, there are parts of New York like Bay Ridge and Brooklyn that are very Palestinian, very Arab. There are Palestinian restaurants, and they have all these Palestinian murals and signs — that's really crazy to see. There are also a lot of organising groups based in New York that I'm trying to get more involved with, which is really cool. There's the Palestinian youth movement, they have a chapter in New York, and it's run by 20-something-year-old Palestinians, so that's really, really cool. They put on a lot of events. Last week, I went to a film screening in the park. They showed two militant films from the 70s and 80s that were rescued from Israeli destruction. So that was really cool to see.

So let’s talk about your artwork, which is just beautiful! What has the process of honing your craft been like for you?

I think I still am! Sometimes I look at my work and think, this is terrible. But I have definitely improved a lot. I think it's the structure of how RISD teaches things. We had very intensive studio classes which ran from six to nine hours a day. It would just be like work, work, work, work, work. It's kind of toxic, to be honest. There is a very strict grind culture and it's the worst freshman year because I think they are trying to weed out people who can't do it. Again, horrible! But in a lot of ways that has helped me get better at drawing. Drawing outside of my art style and figure drawing before I even tried to touch upon more personal stylized illustration work. I feel like the better I get at just regular drawing, the better I get at figuring out what my style looks like in an illustration. They encouraged us to carry notebooks of stuff, go to cafés and draw people and just keep drawing, drawing. Even outside of our studio, we would do that a lot. I've been trying to get back into a habit of doing that but I've felt very drained after graduation so I haven't picked up a notebook and drawn for fun in a while. But it was very helpful to just keep doing that whenever I could and not think about it too deeply. Instead of trying to get something down perfectly, to just sketch it and try to finish it really quickly and see what comes out. Also for this book specifically, since I first drafted it as a senior, I did redraw it entirely by the time publication came around. The year I worked on it for publication, I redrew the entire thing because I felt like I'd gotten better. I wish I could show you the earlier pictures — it looks pretty bad. The initial dummies were ugly and redrawing it was really helpful. I also struggled with colour before, so I worked on that a lot between creating the initial dummy and the published book. So the colour has drastically changed and the way of rendering has drastically changed. I'm still kind of figuring that out but I think I'm at a place now where if I've produced work people can look at it and know that it's mine. I'm happy that it looks a distinct way. But it wasn't like that when I was a student.

If someone reading this aspires to be an illustrator what advice would you give to them?

It's so funny because people are asking me these questions, and I'm like, I'm literally a random 24-year-old, I don't know why I'm being asked these! But I think if you're looking to illustrate for picture books, or children's literature in general, I often see portfolios that don’t have many kids in them. But that’s a really big thing. Publishers will want to see how you draw kids. In terms of finding your voice, I think you need to draw figuratively first before you start stylizing. Drawing quickly really helps you naturally see the way you draw things or the natural way you make strokes on a page. If you’re in a cafe, someone is going to keep moving. You can’t just draw a person standing still at a distance so you are going to have to get that down in 30 seconds to a minute. Doing that consistently, you start to figure out ways of getting it done faster and it naturally starts to become more stylized. It’s a really good way to practice honing your craft as an illustrator.

Who is someone from a SWANA diaspora you find inspiring right now?

Off the top of my head, my friend, Mohammed El Kurd. He was at the forefront of the movement in 2021 when the Sheikh Jarrah ethnic cleansing campaign was a big point in the media because he was the face of that. It was his house getting taken. He wrote a poetry book, and he was a spokesperson for Palestine, for The Nation. I'm super inspired by him. He's an incredible writer and he's unapologetic. He emphasises that he will not be a perfect victim. I think that's super important when we talk about Palestinians. A lot of Palestinians have a habit of apologising for things we never did because our whole oppression is based on things we are not guilty of. He's so unapologetic about that. I really value that, and I really like his writing. But there are many Palestinian artists and writers I love. Naji Ali. He was assassinated in the 70s, but he’s a Palestinian political cartoonist. I think my art style pulls from his. There is also a political cartoonist, Muhammad Sabaaneh, who spent time in prison for his political cartoons. He’s from Gaza and his work is also inspired by Najid Ali’s, and I’m inspired by him. There is a graphic novel called Palestine by Joe Sacco that was published in the 90s. He’s a white man but he started that genre of graphic novel where it is graphic journalism. The entire book is about him being in Palestine and just talking to people and illustrating these conversations. It was the first thing that was ever put out there in the mainstream that was just Palestinians talking. I looked at it when I was in high school.

Amazing! These answers also bleed into my next and final question, which is, what is the one cultural artefact that has changed the way you think about the world?

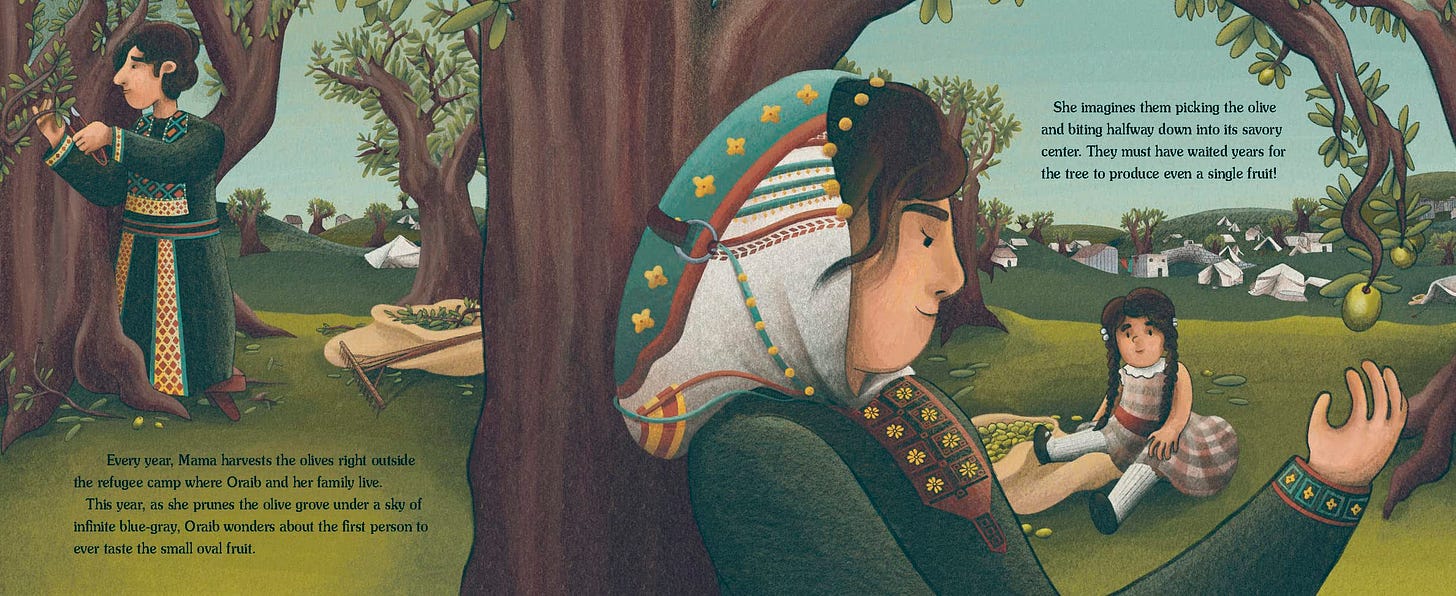

This is kind of personal but I recently discovered a bunch of footage of my family in the 1940s to 1950s. One of my uncle's friends found it and managed to save it. It’s three hours of footage with music playing over it, and it was filmed by one of my great uncles in Palestine before they left. It shows my family across decades. I first saw it a couple of years ago, but I go back to that a lot. It’s on my laptop and I actually used it to draw the characters in my book. I used it as a reference for their clothing. All the clothing in the book is actually directly pulled from the footage I have of my family because that was as accurate as I could get. I was worried about being accurate because there isn’t a lot of documentation of Palestinian attire from that time and I didn’t want to offend anybody. So I just pulled from what I knew, which is my family’s direct archives. So I think that is the most precious thing I have ever encountered. I am so lucky to have that.

That’s so incredible, what a powerful artefact to have. I’m so glad you have it too! Thank you for sharing, Aya.

Thank you — this was great!